This is the sixth SPS post on the subject of the ExxonMobil ‘Solent CO2 Pipeline Project.

The front page summary post, which is the best place to begin for the reader new to the subject, can be found by clicking this link.

Alternatively, the full list of SPS Posts on the subject can be found by clicking this link.

It has been a challenging month since ExxonMobil published its non-statutory consultation documents on the ‘Solent CO2 Pipeline’, creating a steep learning curve for the communities around the Solent. The difficulty lies in making sense of the sparse detail provided with the predetermined solution presented in the consultation materials, which, when coupled with the patronisingly inadequate online response form provided, offers little more than a ‘Hobson’s Choice’ between three equally unacceptable pipeline corridor options.

Look beyond the polished graphics and overly-confident language of the consultation material and it soon becomes clear that this ‘non-statutory consultation’ by ExxonMobil appears to be more about advancing the company’s own agenda than genuinely seeking feedback from local communities. Many of those who have reviewed the ‘document library’ provided with the consultation have been far more concerned by what it conveniently omits than by what it includes.

ExxonMobil’s premature conclusion, evident in its shortlisting of the three land-based pipeline corridor options, clearly exposes its agenda while dismissing any reasonable challenge to its assertion that ‘the solution is a pipeline’.

Solent Protection Society believes that there are fundamental questions which need answers before anybody can be convinced by that assumption:

- What is the real purpose of this consultation?

- What is ExxonMobil’s real motive?

- Does the Southampton to London Pipeline project provide a relevant reference for the Solent CO2 Pipeline project?

- Where does the ‘Solent Cluster’ fit in?

- What other initiatives for offshore CO2 transport are being considered by other consortia?

- What is the Northern Endurance Partnership?

- How can you respond to this consultation?

- How important is political lobbying?

What is the real purpose of this consultation?

As a non-statutory consultation it serves the purpose of satisfying the first step – Pre-application – in the Planning Inspectorate’s ‘Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project’ (NSIP) process.

Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects – The process steps

Pre-application: Before submitting an application, potential applicants must carry out consultations on their proposals. This stage is crucial for gathering feedback and making necessary adjustments.

Acceptance: Once the application is submitted, the Planning Inspectorate has 28 days to decide whether it meets the required standards to proceed to the next stage.

Pre-examination: During this stage, the public can register as interested parties. The Planning Inspectorate will also hold a preliminary meeting to discuss the examination process.

Examination: This stage involves a detailed examination of the application, which can last up to six months. Interested parties can submit their views and evidence.

Recommendation and Decision: The Planning Inspectorate has three months to make a recommendation to the relevant Secretary of State, who then has another three months to make the final decision.

Post-decision: If the application is approved, the developer can proceed with the project, subject to any conditions set out in the Development Consent Order, DCO.

To meet the requirements of a Development Consent Order, a pre-submission non-statutory consultation should be robust, inclusive, and transparent. Information provided must be clear, accessible, and detailed enough to allow consultees to form a reasonable view of the proposed development. Above all, the applicant must be transparent about the objectives of the consultation and the constraints. They should communicate clearly what elements of the project are open to change based on feedback and which elements are fixed.

In our opinion, the format of the online response form provided is not fit for the purpose of ‘gathering feedback‘ which would enable ExxonMobil to make ‘necessary adjustments‘ prior to its submission of an application. The information provided is insufficient to enable a ‘reasonable view of the proposed development‘, with its limited choice of options and a complete absence of detail regarding the upstream (Fawley site) and downstream (injection site) development projects and the viable alternatives solutions for the transport of CO2.

For ExxonMobil, the only answer appears to be ‘a pipeline’.

For these reasons, Solent Protection Society believes that the consultation is both flawed and incomplete and we will be making these points clear in our response.

For our members, our recommended approach to response is detailed in a later section, entitled ‘How can you respond to this consultation?’

What is ExxonMobil’s real motive?

The oil refinery at Fawley was commissioned over 100 years ago by the Atlantic, Gulf and West Indies Oil Company. Esso Petroleum have been running the operation since 1951 expanding the production capacity and the product range with regular changes of plant engineering at the site. At the end of the day, it is acting as a modern-day oil refinery and chemical manufacturing site, but one built on old and tired infrastructure. ExxonMobil has to find another 30 years of life or face the same decision that PetroIneos has had to face at Grangemouth.

Fawley’s life blood is its large proportion of the UK market for low-sulphur diesel and its role as one of the four main supply lines of aviation fuel to Heathrow Airport, delivered via the Southampton to London pipeline. The downside of this production is that the Fawley site has the dubious distinction of being by far the largest single generator of carbon emissions in the Solent region.

The UK Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) and the Department for Business and Trade (DBT) are fully committed to the UK’s transition to a net-zero carbon economy, so here’s the catch: the market for both of these core products must decrease measurably over the next thirty years to comply.

As HM Treasury gains substantial revenue from these core products, it is likely to be receptive to ExxonMobil’s lobbying of DESNZ and DBT for maintenance of current production levels of these high-carbon products, offset by sketchy concepts for the future decarbonisation of Fawley that the company is marketing through its ‘Solent Cluster’ publicity campaign. The Department of Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) is also probably being lobbied through ExxonMobil’s sponsorship of its university partner in the ‘Solent Cluster’.

The Government’s commendable ambition for Net Zero provides a political lobbying button that ExxonMobil will be pressing hard as it prepares to submit its proposal to build a ‘Solent CO2 Pipeline’. With a pipeline construction and marketing project organisation just finished on the Southampton to London Pipeline project, it’s easy to see why ExxonMobil would think that the answer is ‘a pipeline’. However, the company is coming from behind as a late-comer to the European industrial decarbonisation game and as we show below, there are other rather more practical and viable options for the transportation of CO2 from the Solent to available, proven undersea storage sites.

Does the Southampton to London Pipeline project provide a relevant reference for the Solent CO2 Pipeline project?

ExxonMobil clearly believes that its success in delivering the Southampton to London Pipeline (SLP) project will provide a convincing project reference for the Planning Inspectorate, so the question is, “how relevant is that reference?”.

The ‘Southampton to London Pipeline (SLP)’ project certainly demonstrates that ExxonMobil and Jacobs have experience of the DCO process and appreciate the value of that process in securing rights to drive a pipeline across multiple UK Local Planning Authorities. However, the two projects, both billed as ‘Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects’, are very different animals.

The SLP project was accepted as ‘nationally significant’ to enable ExxonMobil to continue to compete for a share of the Heathrow aviation fuel market with Shell and Q8Aviation, companies which import aviation fuel from refineries in Kuwait and Rotterdam. The pipeline connected an existing production supply of aviation fuel at Fawley with a confirmed customer for the product, presenting a solid, end-to-end business case. In terms of public safety, the SLP pipeline typically runs at a relatively low operational pressure, between 70-90 bar.

In comparison, the ‘Solent CO2 Pipeline’ has no commercially quantifiable source of CO2 at one end and currently no licenced or proven viable storage site at the other. It cannot be justified as ‘nationally strategic’ in isolation, without being interlocked within a programme which includes credible and deliverable plans for viable upstream and downstream projects. ExxonMobil’s appointment of the same ExxonMobil and Jacobs engineering and marketing staff that worked on the SLP DCO application will give the DCO application a level of credibility, but we expect the Planning Inspectorate to look rather deeper for the missing detail before accepting the Solent CO2 Pipeline proposal.

ExxonMobil have confirmed that this proposal is for a ‘supercritical’ CO₂ pipeline (with CO₂ in ‘dense mode’ behaving like both a liquid and gas), typically operating at high pressure between 100-150 bar. There are well-documented public safety concerns associated with running supercritical CO2 pipelines and infrastructure near to the kind of residential and environmentally sensitive areas which would be unavoidable on any of the corridors selected.

Where does the ‘Solent Cluster’ fit in?

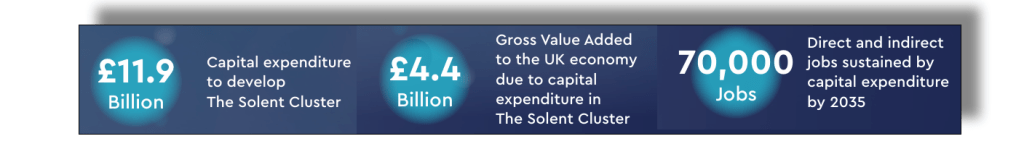

The Solent Cluster appears to be little more than a marketing front for ExxonMobil’s aspiration for the decarbonisation of its Fawley operations. At this early stage, ‘the Solent Cluster’ has delivered little more than a brochure for its ambition, a marketing report which we understand to have been wholly funded by ExxonMobil.

The principal ‘Anchor Projects’ summarised in that report are actually ExxonMobil’s own concept projects for the Fawley site. Developing these concepts into production-ready systems would be dependent on the commercially-scalable production of bio-fuel based aviation fuel and the commercial generation of green hydrogen by electrolysis using renewable energy.

The ‘Estimated Key Takeaways’ present attractive benefits for marketing which are unlikely to withstand thorough scrutiny.

The development, scaling and commercialisation of these new technologies at Fawley is a very long way off and would require massive investment by ExxonMobil, a commercial decision that Ineos and its Chinese partner PetroChina have just rejected for the Grangemouth refinery.

There is clearly good reason to pursue the capture of carbon from Esso Fawley’s current production processes and so there is clearly a need for onsite storage of that captured CO2, a project currently not included in the Solent Cluster set of ‘anchor projects’. However, the amount of carbon to be captured will continue to drop as demand is driven down over the next thirty years, so the justification for a permanent pipeline to an undersea storage site looks weak.

For an independent assessment of ExxonMobil’s future plans for the Fawley site, albeit in the guise of the Solent Cluster’s ‘Anchor Projects’, we refer you to the following Position Statement from Southampton Climate Commission. It’s just four pages long, but contains clear messages and a set of reference sites on the fourth page which are well worth the effort to click through. Click the image below to download the PDF document.

What other initiatives for offshore CO2 transport are being considered by other consortia?

Around the world, other maritime nations are actively pursuing the undersea storage of liquid CO2, with the offshore oil industry majors leading the way through the re-use of depleted oil and gas aquifers to provide the required subterranean reservoirs. Deep sea storage projects such as DeepCStore are active in Australasia and Asia, while the world leaders are to be found just across the North Sea with Equinor, formerly known as Statoil, the Norwegian State Oil Company, and maritime infrastructure companies like Altera.

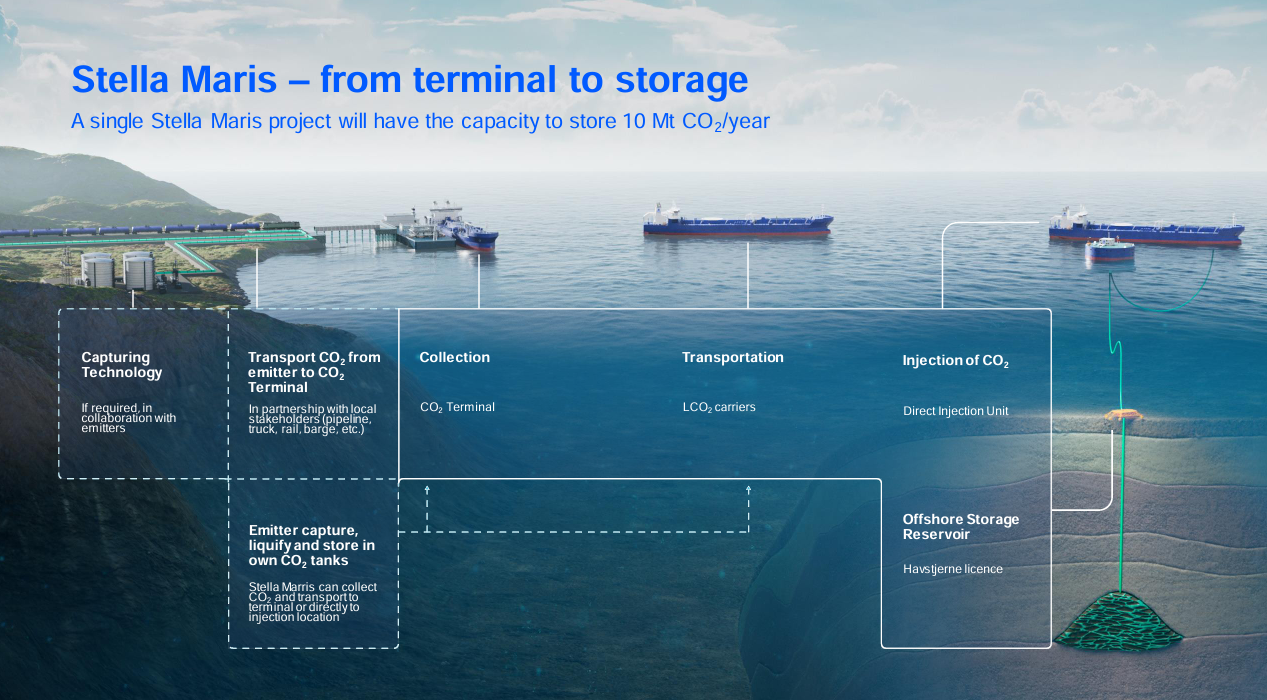

Equinor already manage an extensive infrastructure enabling injection and storage of liquid CO2 into subsea aquifers, either directly via pipeline or via shuttle tankers to offshore floating injection hubs. Altera is focussed on the construction of an operational infrastructure for shuttle tankers and floating injection hubs through its Stella Maris CCS operation. Click the image below to view the detailed presentation from which the image is taken

Elsewhere in the UK, there are other consortia with far more advanced thought leadership than ExxonMobil’s Solent CO2 Pipeline project. Take, for instance, the UK based Northern Endurance Partnership.

What is the Northern Endurance Partnership?

The Northern Endurance Partnership is a consortium closely aligned to the East Coast Cluster and the Teesside Cluster but with members including:

BP – One of the leading companies in the global energy transition and operator of the project

Equinor – The Norwegian energy company with expertise in carbon capture, hydrogen production, and offshore operations

National Grid Ventures – A division of National Grid that focuses on non-regulated activities, including energy transition projects like carbon capture

Shell – The Anglo Dutch global energy company involved in various clean energy technologies, including carbon capture and storage

TotalEnergies – The French multinational energy company contributing to the decarbonisation efforts through CCS and renewable energy initiatives.

To the best of our understanding, ExxonMobil have not yet joined this active consortium. They are, however, members of the Scottish Cluster’s Acorn CCS partnership with TotalEnergies, Shell, Altera Infrastructure’s Stella Maris CCS and the largest London listed independent energy company, Harbour Energy. Harbour Energy declares that, through its relationship with Associated British Ports, it also has potential to provide storage for shipped CO2 from dispersed emitters around the UK and also from Europe.

So it seems that ExxonMobil already has an established relationship with operators capable of removing CO2 captured from the Fawley site without any need for a CO2 pipeline at all.

Which begs the question, why is ExxonMobil’s answer – “A pipeline”?

How can you respond to this consultation?

This is a pre-application consultation for which ExxonMobil is seeking your input. It is also, however, the first step in a process which will enable the company to prepare an application to the Planning Inspectorate for a Development Consent Order under which to perform the work. As part of that application process, ExxonMobil should provide the Planning Inspectorate with the supporting evidence of the consultation responses received.

While ExxonMobil has provided a highly simplistic online response tool at this link, Solent Protection Society suggest that concerned members of the public and organisations should ignore the online tool, and draft their own response without the constraints placed on them by the company, setting out their key points and arguments using the information available from all sources, including the references and comments raised in this set of SPS posts.

Responses should be forwarded to ExxonMobil at the following addresses, before the cut-off time of 6:00pm on 30 September.

Via email, to:

info@solentco2pipeline.co.uk

(Click the link and your email will be set up, including a suggested subject line which you can change.)

Via post, to:

Solent CO2 Pipeline Project,

1180 Eskdale Road, Winnersh,

Wokingham,

RG41 5TU

UK

We would suggest that respondents copy their Member of Parliament on their response, to ensure that their concerns can be made available to the Planning Inspectorate and the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero at an appropriate level. It is the Planning Inspectorate that will decide whether or not ExxonMobil’s DCO is accepted.

How important is political lobbying?

There are many Government ministries and agencies engaged in the decision process, guided firstly by the Planning Inspectorate, an agency of the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. If the Planning Inspectorate accept an application for a Development Consent Order from ExxonMobil, then the eventual development decision will lay with The Secretary of State for the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero, guided by other departments of Government, including the Department of Business and Trade and the Department of Science, Innovation and Technology.

ExxonMobil will no doubt be strongly lobbying each of these departments in order to ensure that the positive aspects of the case for acceptance of its application for a Development Control Order is kept in focus.

The strength of the industrial sector’s influence over UK Government departments should not be ignored.

On 12 September, Amazon revealed its £8 billion plan to establish new data centres in the UK. Simultaneously, the UK Government’s Department of Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) declared that data centres are now classified as ‘critical infrastructure’.

Private individuals and community groups have far less influence, and must rely on their Members of Parliament to express constituency views on the ExxonMobil consultation to the appropriate government departments. If you are concerned about ExxonMobil’s intentions with this consultation, it is important that you keep your MP in the loop and actively request their support.

This is the sixth SPS post on the subject of the ExxonMobil ‘Solent CO2 Pipeline Project.

The full list of SPS Posts on the subject can be found by clicking this link.

To return to the ExxonMobil consultation summary page, click here