This is the fourth SPS post on the subject of the ExxonMobil ‘Solent CO2 Pipeline Project.

The front page summary post, which is the best place to begin for the reader new to the subject, can be found by clicking this link.

Alternatively, the full list of SPS Posts on the subject can be found by clicking this link.

This post takes the form of a series of slides, a format which the Solent Protection Society team has found helpful to elaborate some of the points made in our previous posts on this subject. Zoom into each with a click, or download the set for your own use if you wish.

The well-publicised level of support for the Isle of Wight petition reflects general public anger with ExxonMobil over the impact of the pipeline component of the project on the island. Here on the mainland, discussion with residents along parts of the New Forest route corridor has exposed wider concerns regarding the missing detail of the projects at either end of the pipeline, without which the whole programme of decarbonisation activity has neither value nor purpose.

Our view as a Society is that all three of ExxonMobil’s proposed pipeline routes are unacceptable and that our members on both sides of the Solent are equally concerned about the unjustified threat to the landscape and the livelihood of the local communities. The key message that ExxonMobil need to take from this non-statutory consultation is that the New Forest and the Isle of Wight communities stand together against the company’s proposal, as currently framed.

As we highlight later, the separation of this particular pipeline project from its corequisite projects within the Solent Cluster programme proposition removes any meaningful benchmark for the assessment of its credibility. It appears as a pipeline ‘from nowhere’ to ‘nowhere’, with a premature and ill-conceived consultation which has dug deep into the company’s marketing budget but done little for the company’s public image.

Let’s run through the slides:

The more we research the limited content of the document library, the more complete our conclusion is that this is a flawed and incomplete consultation. The public backlash against the limited ‘shortlist’ of land-based route corridors has been inevitable and should have been predicted, though we accept that inclusion of the two obvious undersea route corridors would not have resulted in any more useable a ‘consultation response’ for ExxonMobil.

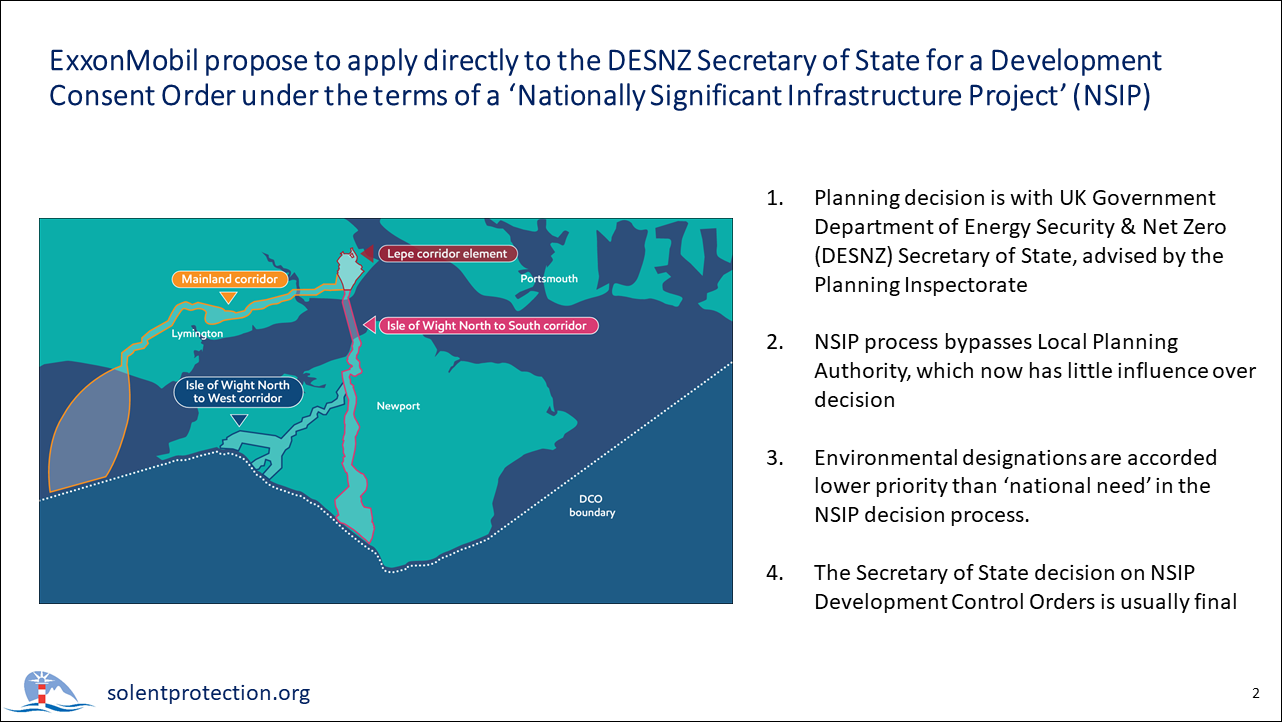

Slide 2 considers ExxonMobil’s proposal to apply for a Development Consent Order using the UK Government’s ‘Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project’ approach. Quite how an isolated pipeline project could class as an NSIP is difficult to see.

Any plan which separates the pipeline from the whole programme of work is likely to be unsuccessful. Under the Habitat Regulations, proposal of a “Plan or Project” that is likely to cause damage to a designated conservation area needs to be accompanied by a demonstration of “Imperative reasons of overriding public interest” (IROPI). We can see that the whole project, to capture carbon, could meet this test but we cannot see how the pipeline alone can meet the test – it has no reason without the rest of the project.

If the company believed that this consultation would win over the public and satisfy the needs of the first step in the DCO application process, then it might just have backfired, dramatically and predictably. ExxonMobil should perhaps look a little further afield along the coast where the general public supported by their local authorities and Members of Parliament has already proven to be tough competition when it comes to questionable NSIP development consent order applications, notably with AQUIND and with Southern Water:

Observer – 13 July 2024

In both of those cases, a vast amount of time and money has been wasted at all levels of government and in communities across the Solent region because of failures by the applicants to carry out basic staff work on the viability of their proposals in the context of the local environment.

This slide (3) should need no explanation given that most readers of this site will be well aware of the sensitivity of the landscape on both sides of the Solent. For those who have not yet explored the MAGIC mapping tool, managed by Natural England and hosted at the Defra website, we encourage you to do so. Here is the link to take and explore.

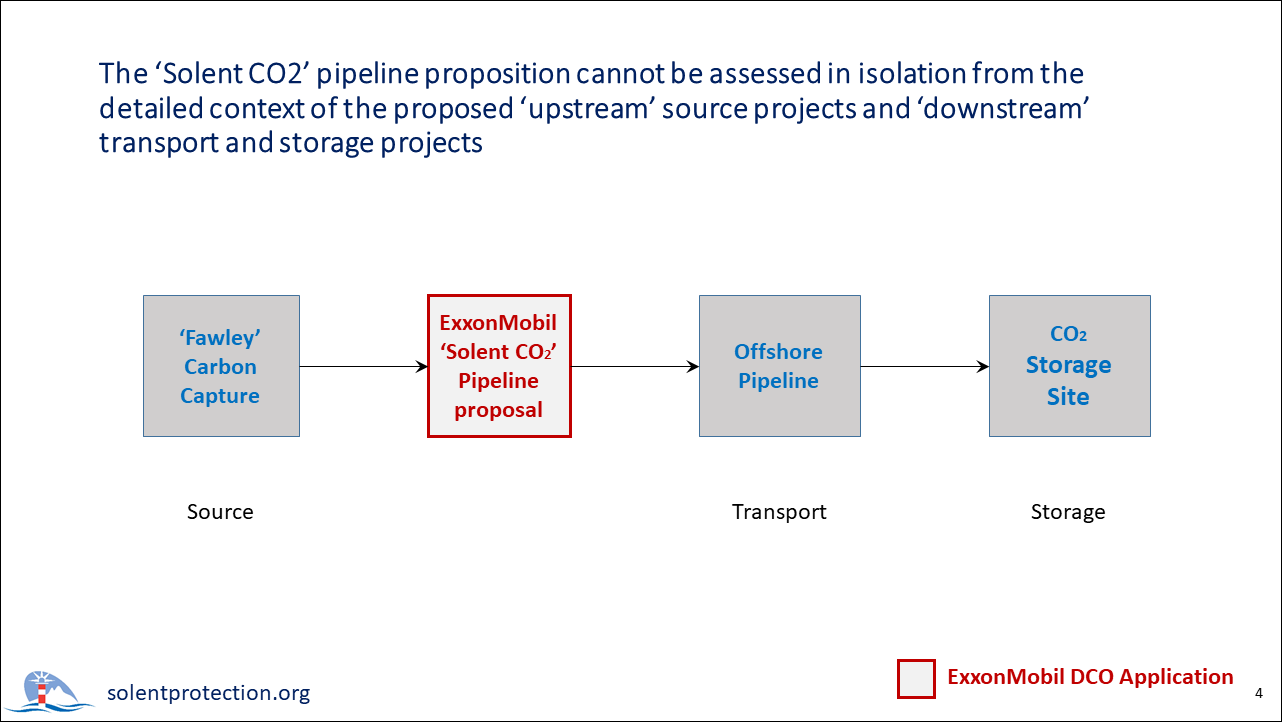

Slide 4 introduces the Society’s issue with ExxonMobil’s deliberate isolation of its ‘CO2 Pipeline’ project from the three corequisite projects that might otherwise give it credibility. The lack of documentation about the projects which will provide the source of the CO2, and the lack of information relating to the pipeline south west of the Island or the undersea storage site itself, leaves us with a consultation about an isolated length of pipeline. Surely an unlikely stand-alone candidate for an NSIP?

These are all good questions which SPS and our members have raised.

Looking a little deeper, this slide highlights the fact that the missing projects are, in fact, the six ‘Anchor Projects’ currently being proposed by the Solent Cluster. You will not easily find them on the Solent Cluster’s website under the site’s ‘Projects’ menu, so we have expanded them for you on the next slide.

(To read a very brief summary of each of the six projects, we’ve included the Solent Cluster ‘Socioeconomic Report’ in a section of references at the foot of this post.)

Slide 6 suggests that there are two fundamental ‘projects’ missing from the Solent Cluster ‘anchor’ set. The first of these is a bulk storage facility for CO2 at the Fawley site or nearby at the neighbouring Fawley Waterside site. The second is the provision of extensions to ExxonMobil’s existing Fawley dock facilities for handling the transport of CO2 – and hydrogen based fuels – reusing LNG (Liquified Natural Gas) tankers.

There is no detail given of the volume of CO2 that could be economically ‘captured’ at source and no assessment of the risk factors behind that estimation. Is the practical use of hydrogen as a fuel anywhere close to being a ‘done deal’ yet? Without certainty over the location and geological suitability of the potential English Channel storage reservoir, is there any point in even considering burying the CO2 at sea here? Why not just ship it somewhere more suitable such as the existing established much larger North Sea depleted oilfield aquifers?

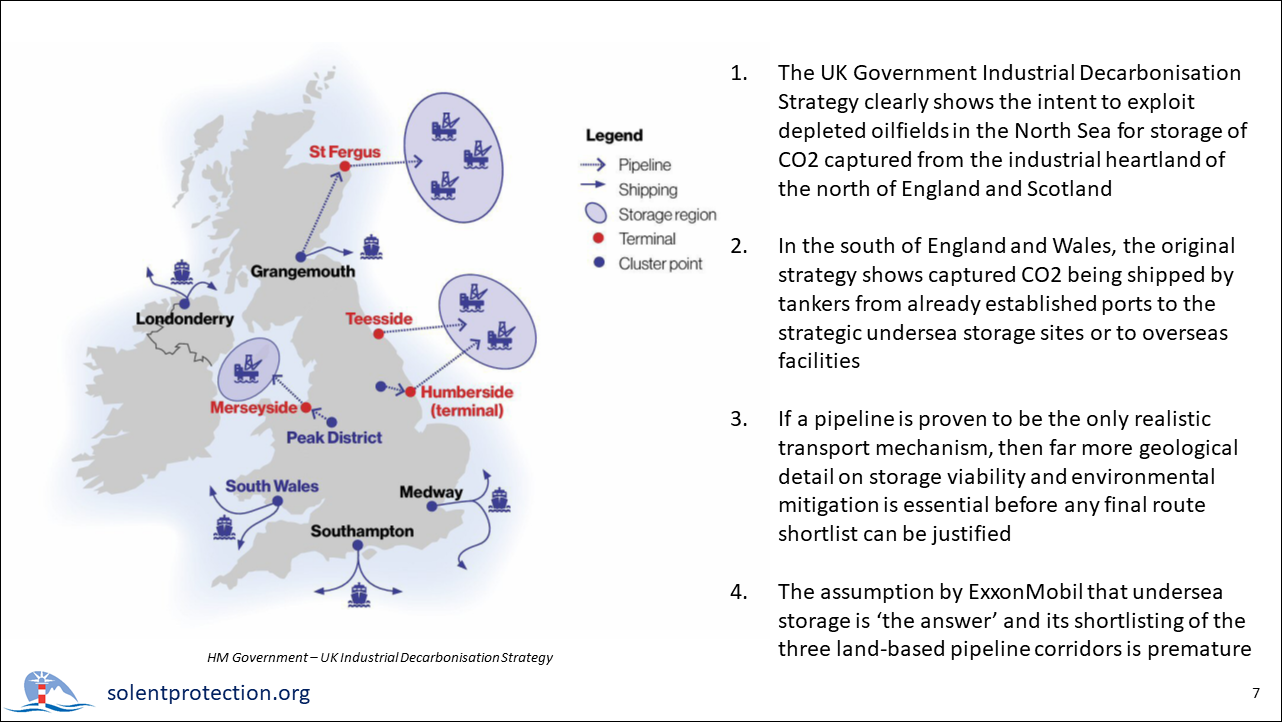

Rather than the current ExxonMobil proposal, the shipping of CO2 by sea is so clearly the obvious transport mechanism that both the Solent Cluster and the UK Government already seem agreed on the point. On the Industrial Decarbonisation Research and Innovation Centre (IDRIC) website, a Solent Cluster source is quoted thus:

“The Solent Cluster has only a small number of major CO2 point sources: ExxonMobil and SSE. Local suitable CO2 storage is being explored but being a key UK port opens an important opportunity to explore CO2 shipping.“

The next slide (7) shows a graphic from the UK Government’s Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy document, which neatly sets out a high level view of the strategy. The ExxonMobil-sponsored pipeline is absent, but the strategic decision to ship by sea is set in a clear geographical context which maps the major industrial CO2 emitters with the reuse of the depleted geological assets and infrastructure of the former UK offshore oil industry. The strategy is clear and the justification for any pipeline south from Fawley seems misguided.

The slide below (8) is taken from a publication by the Carbon Capture and Storage Association and expands on the UK strategic direction, filling in the names of the main industrial ‘cluster’ groups’. We include their individual website links in the table of references and encourage the reader to take the time to review the Solent Cluster online documentation with that of the major, established UK Clusters, particularly those which have already been given the ‘green light’ by the government.

In the latest round of funding announcements from HM Government, announced on 21 August 2024, The Solent Cluster group appears as one of a list of 13 winning projects on the InnovateUK ‘Local Industrial Decarbonisation Plans (LIDP)’ competition, securing funding of £757,000, narrowly beating Bradford Manufacturing Futures to the top of the list.

We note from that announcement that the ‘Port of Poole Maritime Industrial Cluster‘, which curiously doesn’t currently include Perenco, the Anglo/French owners of the Wytch farm oil field, is also developing its own decarbonisation strategy and winning taxpayer funding from the same central LIDP pot.

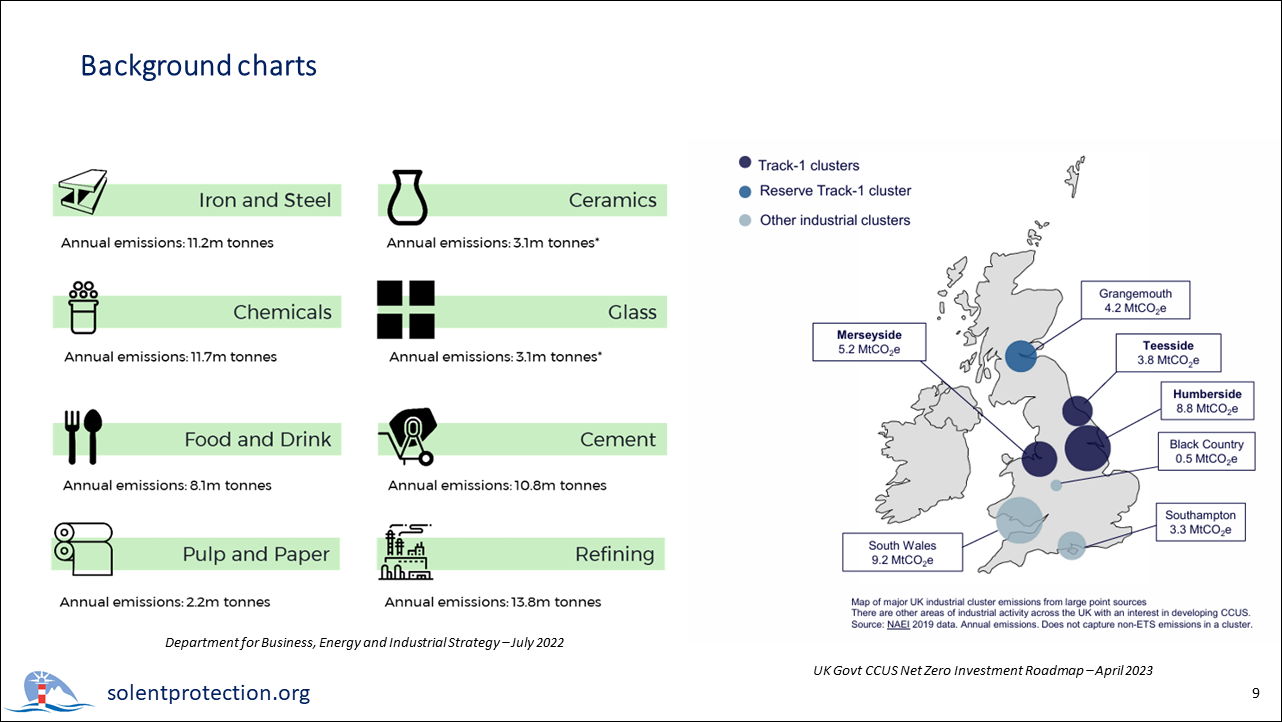

Looking back now to the scope of the industrial decarbonation challenge here in the Solent Region, the following charts may provide helpful background.

The slide above offers two charts from UK Government sources. On the left, a simple explanation of the types of industry that the UK Government believes offer the maximum return on decarbonisation investment.

Refining is the only industry applicable to our area, and so the primary industrial emitter of CO2 is from ExxonMobil’s own facility. That fact is reflected in the next slide (10), which gives a breakdown of the sources of CO2 emission across the main industrial clusters.

The image on this slide (10) is from the UK Government Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy, identifying Southampton as an industrial scale CO2 emitter by virtue of ExxonMobil’s own refinery and chemicals operations which generate the bulk of the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to be captured in the Solent Region.

Emissions from shipping, aircraft and motoring in the region would clearly add to that total, but it would be decades before that emission component could be reduced by the adoption of green technology. While the Solent Cluster ‘anchor projects’ hint at the greening of the refinery operation, there is no relevant detail in the public domain.

Instead of taking the original strategic direction of shipping captured CO2 out by sea in tankers, ExxonMobil’s current consultation shows the region’s principal industrial carbon emitter forging ahead with an untested and unverified undersea storage option which requires massive disruption to the landscapes and habitats of the Solent region.

Once the NSTA grant licences for the evaluation of the English Channel storage site, if they do, there is a great deal of geological investigation required before any quantifiable business case can be established for the overall Solent Cluster programme of projects. There is a clear need for a fully justified geological report, supported by appropriate seismic surveys and drilling, to confirm the type of strata, the risk of fissures and the provision of a firm guarantee that the site will not leak in the future.

Until ExxonMobil and the Solent Cluster come forward with a fully-formed, coherent and deliverable end-to-end programme of projects for the industrial decarbonisation of the Solent region, we will be asking the Department of State for Energy Security and Net Zero to place any Development Consent Order approach by ExxonMobil on hold.

We will be suggesting that our members lobby their Members of Parliament to support this stand.

Acknowledgements and further reading

If you have relevant industrial and/or geological information which could help with our articles, please send via email in confidence, to the following address:

exxon@solentprotection.org

We are grateful to a number of SPS members for their contributions and references during discussions following our previous posts.

For further information, please refer to the following referenced sites by selecting the links.

This is the fourth SPS post on the subject of the ExxonMobil ‘Solent CO2 Pipeline Project.

The full list of SPS Posts on the subject can be found by clicking this link.

To read the next in the series, click here.